Last week, my students and I began our exploration of the pre-modern Mediterranean’s religious mosaic. Our journey began with selections from the Gospels according to Matthew and John. In particular, we discussed events leading to the crucifixion of Jesus and how Jesus might have been perceived by the Romans as well as the Jews who traveled to Jerusalem for Passover, which was about when tradition holds that Jesus was crucified.

What is most striking about these passages—at least for someone like me, who’s read them a million times—is seeing students react to the words of Jesus. Most of my students identify as Christian, but believe that Jesus preached love and compassion. I love that about them. Their Jesus is a very nice Jesus.

So, imagine their faces when we gloss over Matthew 10:34-36:

“Don’t think that I came to bring peace to the earth. I did not come to bring peace, but a sword. I have come so that ‘a son will be against his father, a daughter will be against her mother, a daughter-in-law will be against her mother-in-law. A person’s enemies will be members of his own family.’”

Not exactly the words of a peace-loving Jesus who just wants the world to embrace the Grace of God. But we ignore a lot of the Gospels if we only read that. This is true of much of the Bible. So we shouldn’t cherry pick, should we?

Here’s the thing, though. Sometimes, in history, cherry picking is exactly what people do. And the ancients were no different. For Romans and also for many Jews, Jesus’s words about bringing swords and dividing families, when taken out of context and heard according to how the listener wanted to interpret them, were not metaphorical. They were direct threats to the uneasy peace that the Romans and Jews had built. For them, Jesus was a rebel, a rabble-rouser from the countryside who had a bunch of outcasts for friends. For the Romans and the Jews, his sword was the sword of insurrection.

This is also why the Jews participated in his execution. The Romans, despite their claims of wanting to integrate foreigners into their lands, nevertheless looked down on non-Romans. No wonder, as John tells us, Roman soldiers purportedly adorned Jesus with a crown of thorns and mockingly worshiped him as King of the Jews. No matter what we might want to think about the Romans, they weren’t nice people. But they weren’t dumb, either, which is why they guarded Jesus’s tomb after his death. The only thing worse than a living insurrectionist is a dead insurrectionist whose body goes missing.

But that equilibrium eventually broke down. And I think this is where my students really made some progress and gained some insights into how the ancient Mediterranean was a complex world, equal parts divisive and inclusive.

To this end, we read sections of Josephus’s Jewish War, an account of the Jewish rebellion against Rome that began in 66 AD, which eventually resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem in 70.

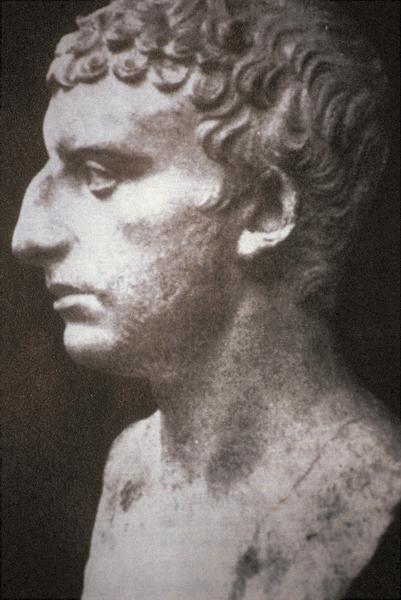

What is most important about this reading, for our purposes, is that Josephus was a Hellenized (culturally Greek) Jew from Jerusalem who at first participated in the rebellion but was captured and taken to Rome as a prisoner. And his brilliance quickly shone through, as he was treated less and less as a slave and more as an archive to mine about the inner workings of the rebellion. He eventually earned Roman citizenship for his cooperation.

Hence his Jewish War.

It’s a great pairing with the Gospels. First, the section we read also takes place during Passover. Second, it encapsulates well what Jerusalem looks like when Roman rule isn’t supported: overcrowded and starved, under siege. Third, it lays bare how complex this religious landscape truly was.

The first thing my students recognize is that Josephus is writing for Rome. He speaks so highly of Roman might, of the magnanimity of Titus, and of the depiction of Jews as terrorists, partisans, and rebels. The students think nothing of it, really. For them, the war is clearly the Jews’ fault. Rome brought them so much, and even killed Jesus for them!

But then, when they are reminded that Josephus is a Jewish prisoner of war, things change.

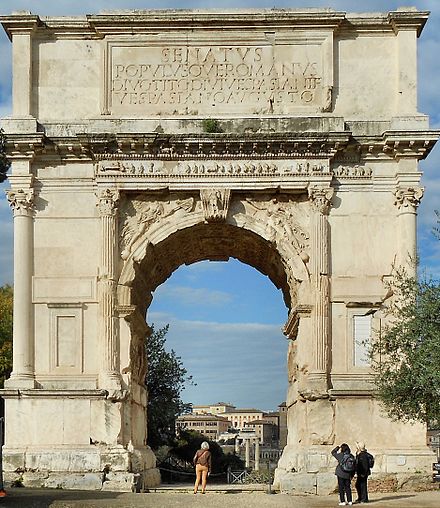

Titus’s troops disobey, which makes him look weak. Roman soldiers are depicted as lustful, bloodthirsty monsters. Rome looks like a tyrannical, imperialistic juggernaut that thinks conquest is a form of liberation. In the end, Titus torches the whole city and brings its spoils back to Rome, hardly the act of a generous leader who wants to bring peace. No wonder peace was not what Jesus was bringing.

What stands out as we concluded our discussion of the Gospels and Josephus is that both readings resonate with several audiences. Sure, the Gospels are explicitly for Jesus’s followers, but the events they recount allow us to empathize with Jesus’s Roman and Jewish detractors as well as their mutual antipathy for and anxiety of one another.

As for Josephus—a Hellenized Jew writing under Roman authority—he celebrates Rome and its might while also laying bare its hypocrisy. He writes a history that speaks to both Romans and Jews without alienating either. He celebrates Rome’s conquest of Jerusalem while preserving the integrity of the Jews’ motivation for rebelling. He likens Rome’s actions to those of the Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks. The Jews withstood them, so Rome will be no different. It’s a masterful work of historiography.

What was great for me was to see the students recognize how complex writing about the past can be, and how the many layers of Mediterranean history converge in the everyday lives of its people.

The students thought that Josephus was brilliant for his ability to both challenge Rome while purportedly celebrating it. And they thought it was cool that he could somehow be culturally Greek, religiously Jewish, and politically Roman. The inability to disentangle the three was, for a group of freshmen, equally mind-boggling as it was insightful.

With any hope, I may have created a few Mediterraneanists. Time will tell. But in either case, it was a great start to the semester.