This June, I’m guiding a group of fifteen students from Western Carolina University to Rome. For some of my students, it’s their first time leaving the country; a few have never even been on an airplane! For me, it’s a great opportunity to share my love for Rome with a group of students and renew my passion for the Eternal City. That’s not to say that I’ve grown bored with Rome, but I’ve seen the Colosseum a million times; it’s still awe-inspiring, but not quite like it was the first time. I hope to see that joy in my students’ eyes. Maybe I’ll feel like a 19-year-old again.

As someone who always thinks about the Mediterranean (literally, all the time; it’s a problem, especially when it comes to Mediterranean food), this trip is a great opportunity to show how Mediterranean history works locally. Rome’s the perfect spot for that. It’s not just a palimpsest of historical eras, but it’s also a crucible of Mediterranean cultures past and present. The city is festooned with artifacts that lay bare the myriad peoples from Spain to Syria who’ve visited or called Rome home. It’s here that I hope to show my students how Rome is both in the Mediterranean but also of the Mediterranean.

What do I mean by that? What does being in and of the Mediterranean mean? Well, here are a few highlights of the trip that show you.

Take the Basilica of San Clemente. It’s located about halfway between the Colosseum and Rome’s cathedral, St. John Lateran, which was largely built through the largess of Rome’s first Christian emperor, Constantine. San Clemente, when you enter it, is a typical Roman church: the apse has a beautiful early-13th-century mosaic in a typical Byzantine Greek style.

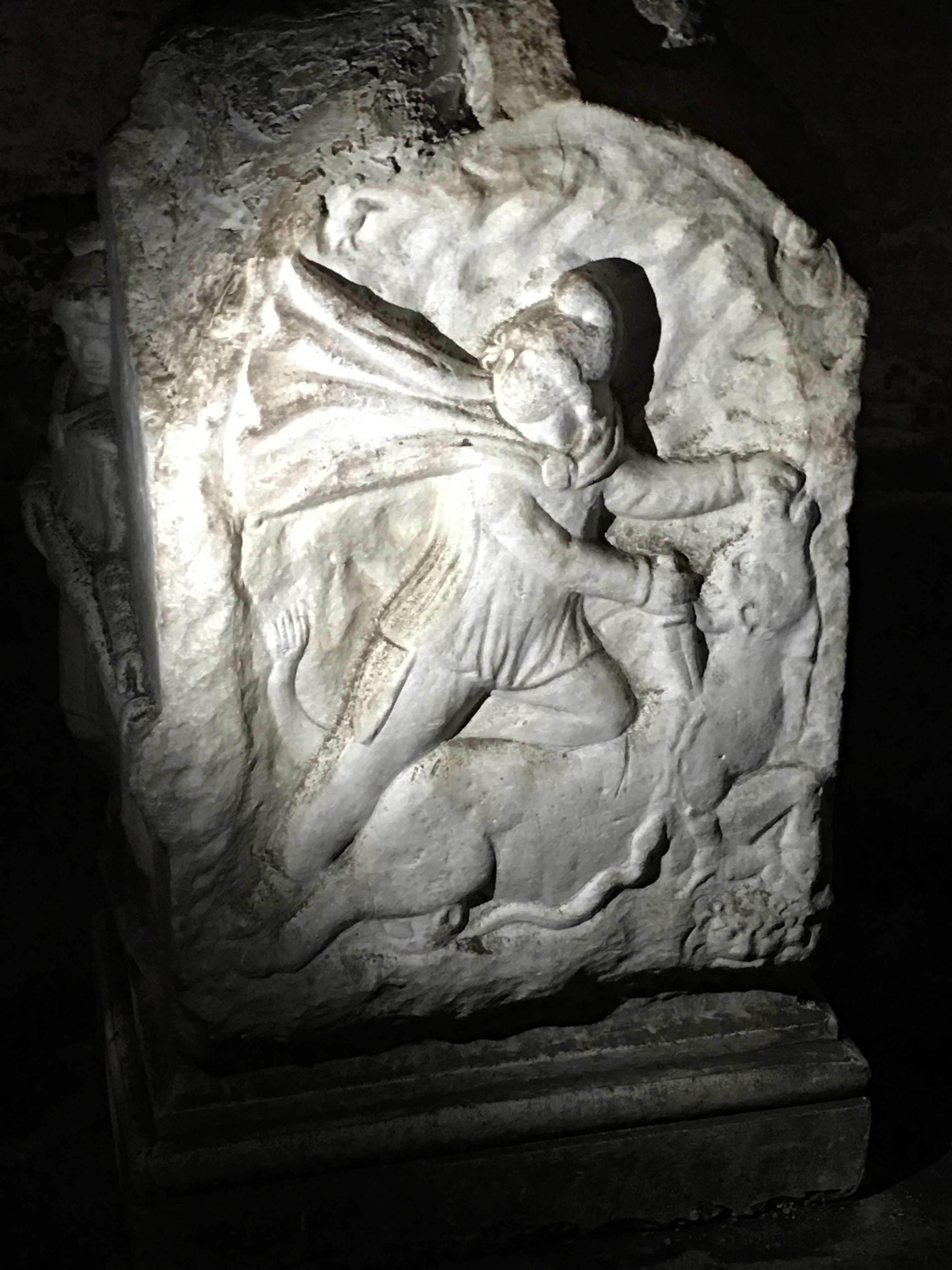

But below the church are a few treasures that you can see for a nominal entrance fee that goes toward maintenance and restoration: a 4th-century church as well as an even earlier temple, probably from the 2nd-3rd century, dedicated to the god Mithras, a mysterious figure about whom we know very little. But we do know that his cult originated in Persia and probably migrated throughout the Roman Empire via its mighty military, where it was made more palatable for Greeks and Romans.

All of this means that, within one structure, we have layers of the past as well as layers of the Mediterranean. Worship within Rome, in one space, ranged from Persia to Greece to Italy and beyond.

Another church, probably one of my favorites in the city, is Santa Maria in Cosmedin. Originally built in the 6th century, it was (and still is) a centerpiece of the Greek-speaking community of Christians that operated in Rome since antiquity.

In fact, the church’s name “Cosmedin” originated probably from the Ancient Greek word κοσμίδιον (cosmidion), which is related to our English words cosmos and cosmic. The church basically is called Saint Mary in the Cosmos or, if you’re feeling silly and are okay with loosely translating things, Cosmic Saint Mary!

Most people don’t even go into this church. It’s perhaps best known for the Mouth of Truth, an ancient sewer cover that allegedly bit off the hands of liars. Tourists line up just to test their honesty, just as Audrey Hepburn did in Roman Holiday. I once took my fiancée there and asked her if she loved me just as she put her hand in. She still has two hands, so we might be okay.

In any case, skipping the inside of this church is a travesty. It’s austere and lacks the wow factor of most of Rome’s baroque churches, but it’s gorgeous in its simplicity. It has these lovely stone floors arranged in a style known as cosmatesque, an elaborate form of floor mosaic that, while thoroughly Roman, nevertheless betrays its Byzantine roots.

Likewise, it has ancient columns that are not uniform by any stretch, but clearly serve an architectural purpose. In late antiquity, it didn’t matter if the capitals matched, just so long as buildings didn’t fall over. But the capitals are all of different styles, showing that architecture in Rome was a mishmash of styles and tastes.

I could go on with examples that show how Rome was and is as Mediterranean as it gets. From Arab-style bowls in Romanesque bell towers to the more than 2,000-year presence of Jews in Rome, it’s a city that lies at the center of the Mediterranean in a number of ways.

Whether it’s food, architecture, or any other aspect of Rome, the Mediterranean has shaped Rome as much as the empire Rome built shaped the Mediterranean. If you want to be in the Mediterranean while also understanding the history of the Mediterranean, look no further than the first city to unify it all. When the Romans called it Mare Nostrum, Our Sea, they were right; they just didn’t realize how much the Middle Sea shaped their world.