Toward the end of the Middle Ages, the popes left Rome for southern France. In 1420, however, Martin V returned to Rome and began the long process of turning it into the city we now know: one of churches, palaces, and wide avenues.

Taking the students through the Rome of the Renaissance Popes is one of my favorite parts of the trip. Not only does it mean I get to talk about some of my own research, but it also means I get to re-visit some of my favorite pieces of art!

Renaissance Rome is a monumental city. It’s St. Peter’s, the Vatican Palace, obelisks, massive palazzi. I love showing the students all that Renaissance Rome has to offer. We start small(ish) and then finish with a bang. This is just a sampling.

The first place I take students is Villa Farnesina, which was built by the Sienese financier Agostino Chigi. Chigi made his fortune as the banker to Pope Alexander VI, as well as monopolies on salt and alum, a crucial element for textile manufacturing. Built between 1506-1510, Villa Farnesina was Chigi’s pleasure palace in the Roman neighborhood of Trastevere. It has wall frescoes from painters such as Raphael, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Giulio Romano.

I love Villa Farnesina for a lot of reasons. The amazing frescoes in the Loggia di Psiche or the grotesque paintings in the stairwell tell us a lot about Renaissance tastes and how individuals like Agostino Chigi wanted to live in lavish homes. I especially love to point out to students how some of the earliest depictions of foods from the Americas are in the frescoes of Villa Farnesina.

But Chigi’s wealth pales in comparison to the popes’. From Trastevere, we walk toward the Vatican, stopping off at Castel Sant’Angelo. Originally built as the mausoleum of the Emperor Hadrian in the second century AD, it was converted into a fortress in the Middle Ages. In the Renaissance, it was linked to the Vatican by a walkway atop the city walls. During the 1527 Sack of Rome, Pope Clement VII hid here along with the painter Benvenuto Cellini, who claimed he killed the attacking commander with a single shot. It was also a formidable prison, housing famous prisoners such as Cellini and Giordano Bruno. It’s now a state-run museum that hosts a number of rotating art installations.

I really love Castel Sant’Angelo. I enjoy walking the walls and seeing the many rooms of the castle. There’s even a wonderful cafe, which is a great place to grab an Aperol Spritz or Negroni before dinner as the sun sets. The highlight is climbing to the terrace, where you can get a panoramic view of the city, including a direct shot to Saint Peter’s Basilica.

From Castel Sant’Angelo, it’s a short walk to the Vatican. The Vatican Museums, I have to admit, are a struggle to visit. They are very crowded, and much of the experience can feel like you’re being herded like cattle. But it’s a must any time you’re in Rome.

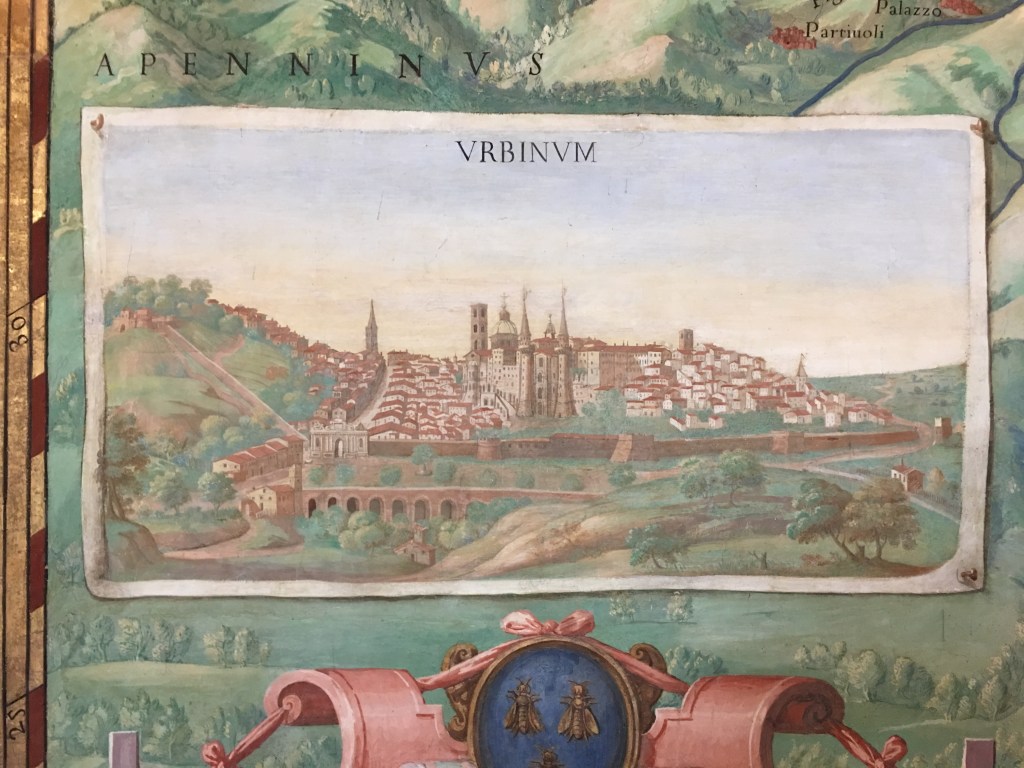

There is so much to see. The Vatican Museums are in what were the major parts of the Vatican Palace, where the popes still reside. I personally prefer to check out the Galleria delle carte geografiche, with its dozens of 16th-century maps of Italy. I also stop and gaze at the Laocoon, a Hellenistic sculture group discovered in a farm in Rome in 1506. It’s my wife’s favorite, and students love it too. It tells us so much about what the Romans appreciated in art, and it came to be a major influence on Renaissance art as well.

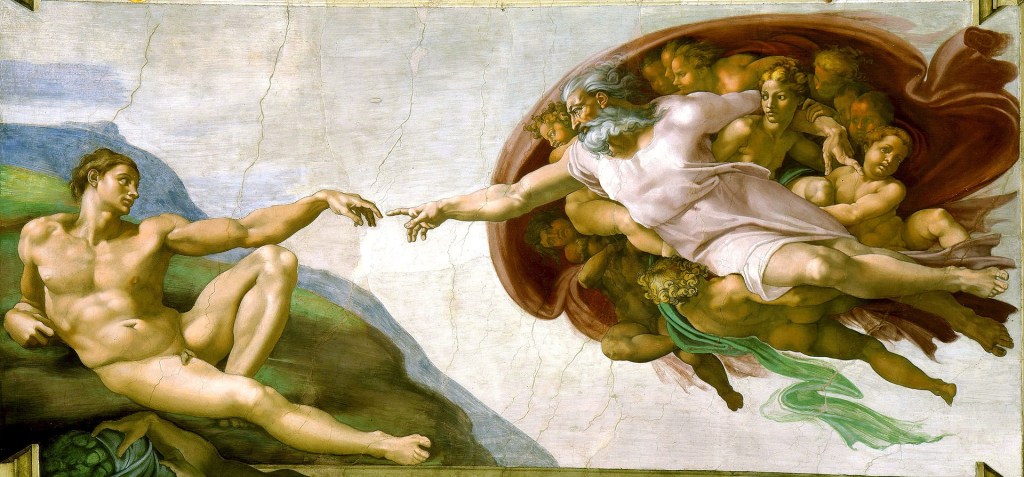

The highlight, of course, is the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo’s masterpiece. There really is no way to capture what it’s like to experience the Sistine Chapel. Its depictions of Old Testament scenes will leave you with a neck ache as you try to look up at stare at them. It’s almost impossible nowadays, but years ago I got in with a small group and had the chapel to ourselves. It was really something else.

With students, I like to linger in the chapel and let them really soak it in. The students could spend all day in there, and honestly I could too. Unfortunately, as is so often the case in the world of mass tourism, the Vatican Museum guards have other ideas, and usher us out seemingly as soon as we entered. But for a brief 10 minutes, we are in heaven.

Or so we think! Because truly, there is nothing like walking into St. Peter’s Basilica. If you ever want to feel small, I mean immensely small, so small that you question how much room you actually take up in the world and whether your existence is ephemeral, enter St. Peter’s. It is, simply, massive.

What always shocks me every time I enter Saint Peter’s is just how much of a testament to human engineering it truly is. With no modern technology, stonemasons, goldsmiths, architects, artists, sculptors, you name it, came together to build a church that is worthy of its patron, the legendary founder of the first Christian community in Rome, Peter.

Walking around St. Peter’s can take hours. There is so much to see: Bernini’s baldacchino and cathedra; Michelangelo’s dome and Pietà; Arnolfo di Cambio’s bronze St. Peter’s, whose foot is worn down by the kisses of pilgrims. For me, nothing beats standing there quietly and taking in the immensity of the space.

After a while, students begin to flow out the main doors and into the piazza, which is worth checking out in its own right. We meet at the obelisk, where we hang about for a bit and talk about everything we saw. Students like to check out Bernini’s colonnade and listen to the waters of the fountains trickle in the hot sun. I’m usually the last one out, as I like to do one last lap or two inside St. Peter’s, which I could probably visit every day, if they let me.

After a full day in Renaissance Rome, we’re all exhausted, and ready to take a long break from the heat and crowds of Rome. Which we will do. Up next is a day trip to Tivoli to check out two villas: Villa d’Este and Villa Gregoriana. It’s the perfect way to recharge.