Over the past few weeks, prep for my travel course to Rome has ramped up. I’ve begun writing lectures, compiling visuals, and—by far my favorite part—mapping out our walks. Right now, my current darling is our walk along ancient aqueducts and the Via Appia Antica.

I love this walk because it’s a reminder that Roman history is Mediterranean history on several levels. We look at how Rome used the surrounding landscape to provide the city with water both to drink and to admire. Then, we put to test the old adage that all roads lead to Rome by walking on one of its oldest and most famous: the Appian Way.

First, we start in the Parco degli Acquedotti, some ruins of aqueducts that now are the centerpiece of a rather lovely public park. The two main aqueducts that pass through this park, the Aqua Felix and the Aqua Claudia, pumped clean, fresh water into Rome. The Aqua Claudia, build by Caligula and then Claudius in the first century after Christ, demonstrated the ingenuity as well as the prosperity of Rome, as the city of 1 million residents needed water but also needed everyone else to know they lived in the capital of the world.

The Aqua Felix, better known by its Italian name Acqua Felice, was built by Pope Sixtus V in the 1590s. His first name was Felice (happy or lucky), which gives you a sense of Sixtus’s sense of himself. It’s an attempt to prove the booming Baroque city with much needed drinking water; but it’s also designed to revive and reflect its predecessor, the Aqua Claudia. It bring potable water to the city, but it also fuels some of the city’s great fountains, such as the Fountain of Moses. Sixtus’s goal was to turn Rome into a global capital, and this was one way he did it.

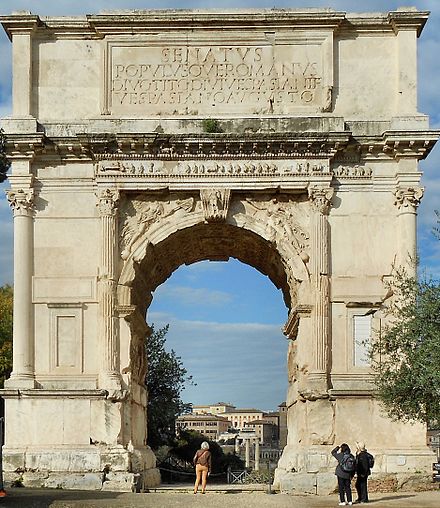

From the aqueducts, we cut through a pretty unattractive suburb to get to the Via Appia Antica. We begin the walk toward Rome by admiring the many tombs, much of which are copies, that follow the road. In ancient times, the rich and powerful, but not just, wished to be remembered in this life by having passers by stop to admire their tombs. Many of these tombs actually invite the traveler over to pause and contemplate the lives the dead lived. It’s a reminder that the dead are still with us, even 2,000 years later, and that the living’s concerns about their legacies have changed very little.

We then pass by an archaeological site known as Capo di Bove, which means Ox Head. This is what it was called in the Middle Ages. In ancient times, it was home to a thermal bath. While almost certainly a private bath, I sort of like to think that its owner offered travelers a nice respite on their approach to Rome. But this is usually more my tired feet talking than what I as a historian know about how things worked in the past. Either way, the baths were a big part of Roman social life and could be found, both in public and private forms, all over the empire. The city Bath in England is named because of its extensive baths the Romans built when they put down roots there.

After Capo di Bove, we pass by the tomb of Caecilia Metella, who was the wife of Marcus Licinius Crassus, the son of Marcus Crassus, one of Julius Caesar’s soldiers and once seen as the richest man in Rome. The sheer size of the tomb illustrates her wealth and power as a patrician wife in the first century. Her family, the Caecilii Metelli, were insanely powerful too. With estates across the Mediterranean, these two families’ political alliance through the marriage of Caecilia and Marcus only magnified their influence and their ability to build on a massive scale.

We then plan to stop for lunch at the Circus of Maxentius. Maxentius is best known for losing Rome to Constantine in 312 at the Milvian Bridge. But before he did that, and ceased to be emperor, he built a private country villa along the Via Appia, along with its own circus for chariot racing. Talk about megalomania! Imagine having a private horse racing track in your own back yard. It’s mostly ruins now, but it’s a nice spot for a picnic.

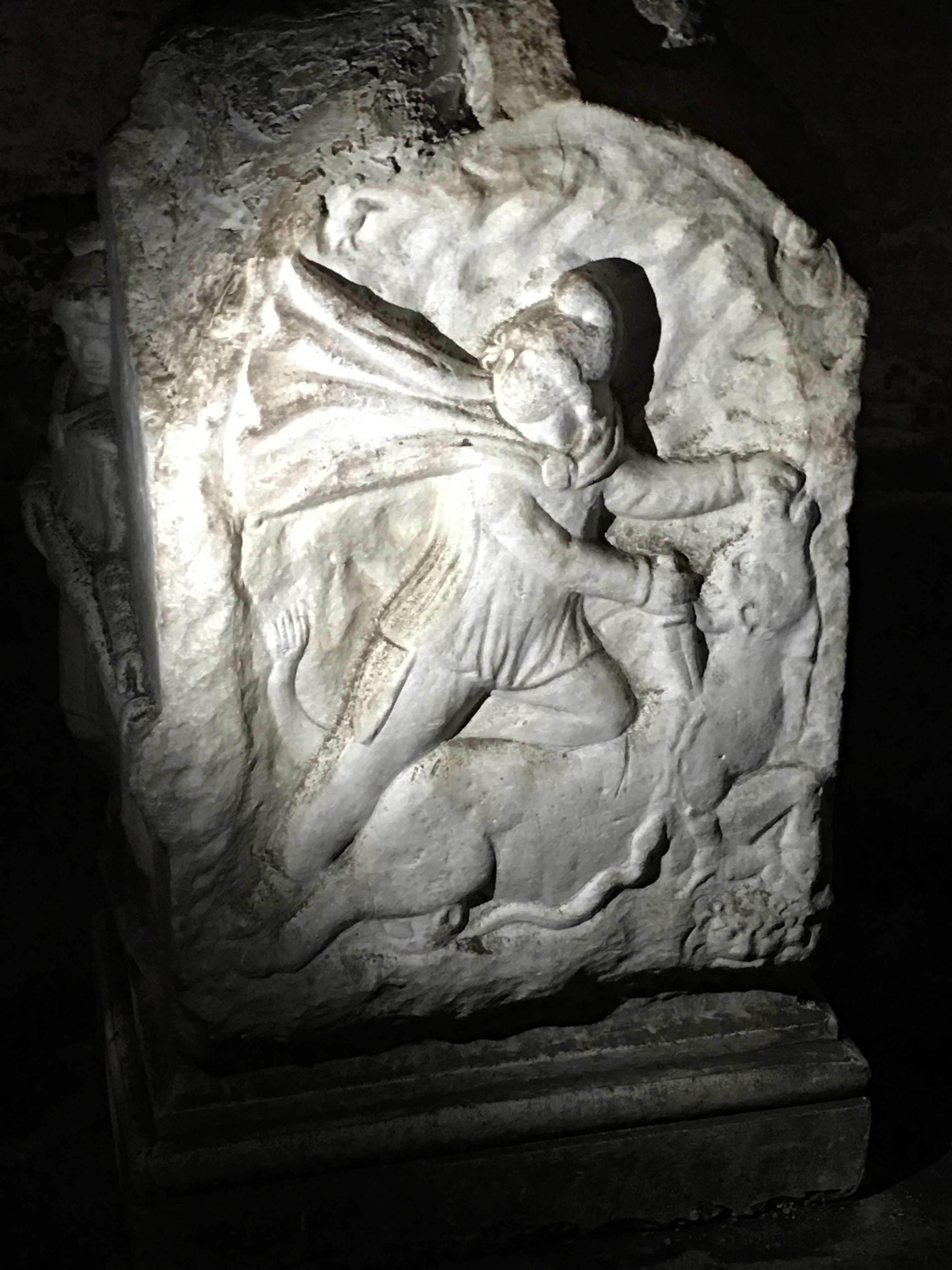

After we recharge, we’ll stop at the Church of San Sebastiano, which has some really wonderful Christian catacombs. Once believed, falsely, to be Christian hiding spaces, the catacombs are great to explore how the earliest generation of one of the Mediterranean’s youngest religions, Christianity, survived and thrived in a world dominated by Rome’s civic religious life. While Christianity began in the Middle East, it did not take long for it to spread across the Mediterranean, and to Rome in particular. The catacombs are also great in the summer, because they’re under ground and about 10-15 degrees cooler. From San Sebastiano, we pass by the Church of Domine Quo Vadis, which commemorates the moment when Christ urged Peter, who was fleeing Rome to avoid persecution, to turn back and continue his work, even if it would lead to death.

We then will pop into the Museo delle Mura, a tiny museum that is housed within the Porta San Sebastiano, one of the city’s old gates. It’s a quaint little museum, and you can walk along the walls and climb to the top of the turrets of the gate. With spectacular views of the countryside to Rome’s south, it’s easy to get lost in time and think you’re looking out at Rome’s first frontier with the same eyes as those who once defended imperial Rome.

Technically, then, we are no longer outside the city. Our final destination is the Circus Maximus, now little more than a field used for jogging and walking dogs. On the way, we pass by the Baths of Caracalla, a massive structure that once housed a public spa, built in 217. We used to believe that Rome was in a free fall by the third century, but it’s hard to argue that when you look at the testament to Roman engineering, power, and sophistication that stretched across the Middle Sea.

So, that’s our walk. It’s a fun walk and one that lays bare all that Rome has to offer. Plus, it’s outside the city and not nearly as crowded (though hardly empty) as, say, the Colosseum. In just about 3 miles, we’ll learn so much about the Mediterranean: its myriad religious traditions; monuments of Roman power; how commerce worked; and how people communicated and moved in the pre-modern world.