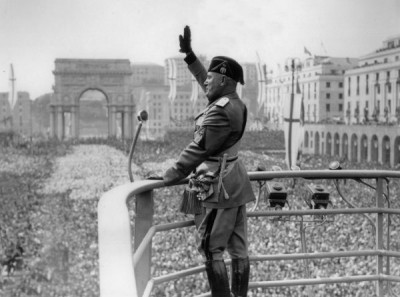

In October 1922, more than a decade before Adolf Hitler claimed power in Germany, Benito Mussolini marched on Rome, ushering in one of the darkest periods of Italian and European history.

Disillusioned with the fallout of the First World War, many Italians rallied behind Il Duce and his promises of a better future. It was a regime based on bluster, fictive might, and a palpable anger grounded in a young Italy’s belief that it was not given due respect.

These promises, of course, were unrealistic and deeply dangerous, as the course of the Second World War would show.

Not everyone was on board with the Fascists, however. Not everyone saw World War I as evidence of Italy’s unfulfilled potential. Some saw it, and war in general, not as proof of a nation’s potential greatness, but of our collective failure.

One such man was the artist Massimo Campigli. Enlisted in the Italian war effort in 1916, he was captured and spent most of the war as a prisoner in Hungary.

But he wasn’t angered by the failures of Italy or its allies. Rather, he was angered by the failure of humanity that is war. He saw its futility, its pointlessness, and, above all, its callous disregard for human life. He realized that, in war, there are no winners. There are only broken promises and failed futures.

While originally linked with the Futurists, some of whom came to support Mussolini’s regime, Campigli rejected their pomposity. Instead, he turned to more subtle, nuanced art.

No work captures this better than his Le spose dei marinai (The Wives of the Sailors, 1934), a work that a few years ago was at the center of a segment in BBC’s Rome Unpacked, hosted by art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon and chef Giorgio Locatelli. It’s a poignant work. The longer I look at it, the more I see the deep melancholy in the women waiting on the shores of Italy, hoping their husbands return alive. Women are told to wait for their husbands, who are sent off to defend the Patria, the fatherland. But they wait. And wait. And wait. The only comfort they find is in embracing each other, as they stare out at a tiny strip of blue, a sea that never gives back.

There’s a deep melancholy in the scene where Graham-Dixon and Locatelli stare at the painting. A quiet room, light shines solely on the painting, and they mull over what would ever happen to the sailers whose wives await their return.

In Italian, there’s an idiomatic expression, ‘far promesse da marinaio,’ to make a sailor’s promise. It means more or less, an unfulfilled promise. A sailor’s promise is made by one who cannot guarantee that what is said would ever happen. The sea into which one ventures does not care about love, promises, futures. A sailor’s promise is a promise broken as it’s made.

So it is with war. Le spose dei marinai are for Campigli le vedove dei marinai… sailor’s widows.

And this is where I feel the most despair when looking at this painting, and where in Rome Unpacked we’re reminded that art’s beauty is sometimes found in how it surreptitiously points us to humanity’s ugliness. All of these women know that some of their husbands will never come home, but none know who that will be. They linger, they hope, they hold on to false promises that will go unfulfilled.

War is anonymous, as anonymous as the women whose faces we never see because they stare out into a Mediterranean abyss.

War is fought in the name of the nation, but those who suffer don’t always do so collectively. Loss is purportedly collective, where we can come together as one (think tombs of unknown soldiers); but once the homecomings end, the bereaved are usually abandoned.

Nationalism, totalitarianism, and fascism are some of those sailor’s promises. We stand on the beaches of sameness and stare out at difference, hoping to finish better than we started. But we never do. Nationalism is an empty identity. The waves roll in, but they do not fulfill our baseless hopes of grandeur.

Campigli captured that in Le spose dei marinai in 1934, five years before war broke out. Had we listened to him and those who rejected fascism and false dreams of empire, maybe the Second World War would have never happened.

But we can learn from Campigli and from his sailor’s wives. There is hope for us in their despair.

He didn’t paint because there was no hope. Rather, he wanted us to believe in solidarity and in our shared humanity. He saw what many of his contemporaries did not see. He was, to borrow Locatelli’s word for Campigli, a lungimirante: far-sighted in the truest sense. He saw what we couldn’t because of our collective blindness.

Solidarity and collective belonging need not devolve into evil, oppression, and destruction. We can do better. I hope we do better. We must do better.

No one wins in war; no war is good, not even just ones. They are the moral failings of humanity that leave us on beaches hoping the sea gives us what it never will.